Engage

Statistical Analyses and Scientific Papers

Statistical Analyses

Science is statistics. Statistics is science. In order for researchers to deem whether they have produced a “significant” result, whether an added compound has caused a “significant” effect, or whether an administered drug has induced a “significant” change in a patient, they must go through statistical analyses. Nowadays, most statistical analyses don’t require lengthy calculations and can instead be computed through common softwares such as Microsoft Excel.

Two common forms of statistical analyses are the “Student’s t test” and the “Chi-squared test.”

(1) Student’s t test

In simple terms, the Student’s t-test determines how probable two samples are the same or different with respect to a selected variable. This test assumes that the data in the two samples were independently drawn and that the amount of variation in the two samples is equal. The “Analysis of Variance” (ANOVA), also another common test, is similar to the Student’s t test except it compares the data among three or more samples.

(2) Chi-squared test

The Chi-squared test determines if the distribution of observations in an experiment has significance. how probable two samples are the same or different with respect to a selected variable. While the Student’s t test tests for a variable among two samples, a Chi-squared test involves two independent variables. A large Chi-squared value entails that either one observed data value has a big variation from the expected data value, or several observed data values vary moderately from the expected data value.

Scientific Papers

A scientific paper typically consists of these sections:

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion and Acknowledgement

References

Figures

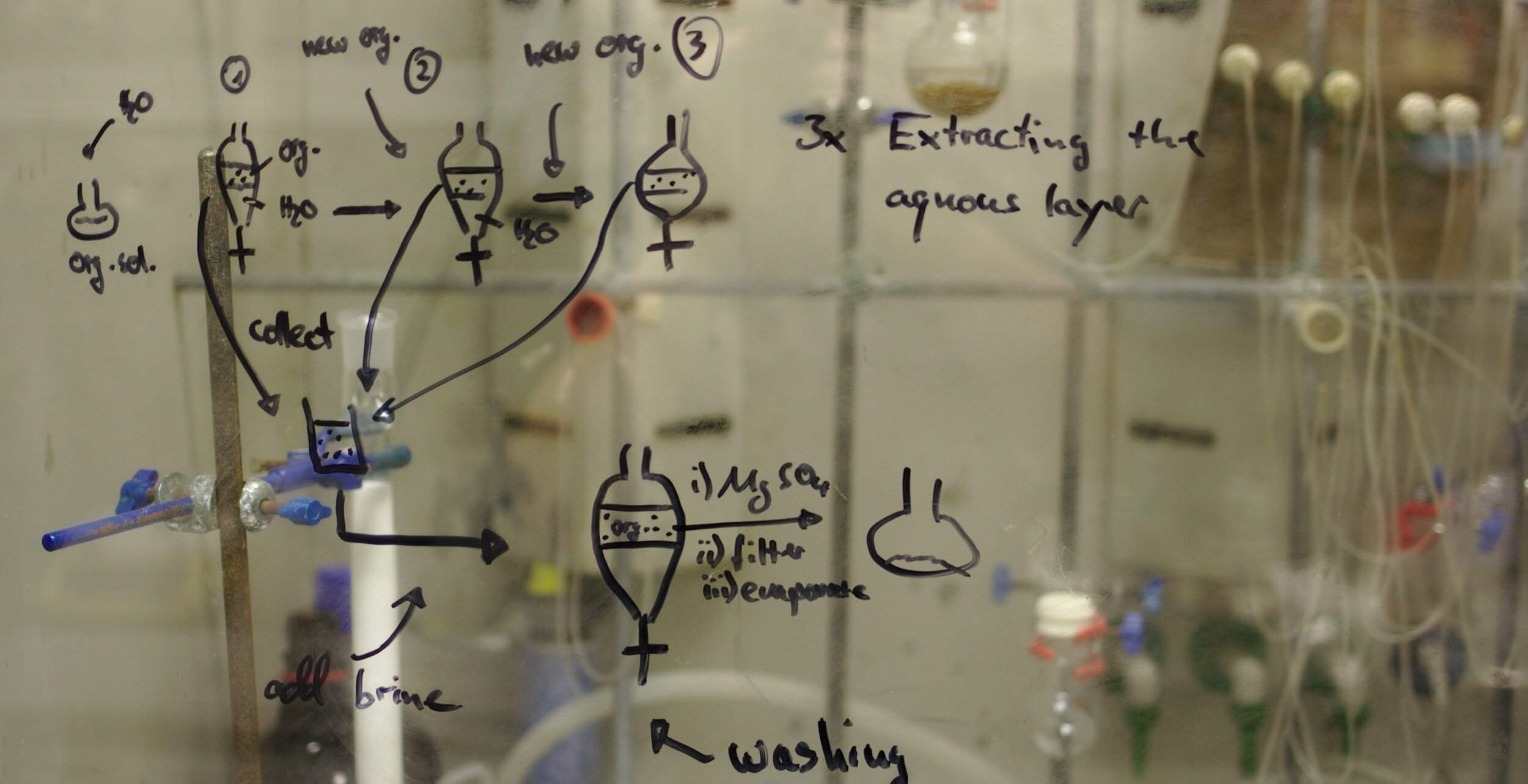

As a high school student, chances are you wouldn’t understand the specific protocol steps of a group’s methods, or be able to interpret their results in a meaningful way. Thus, I find that the most effective way to read a scientific paper as a non-expert is as follows. First, reading the abstract can give you a compacted overview of the entire study, including its motivation and implications. The authors will consolidate their entire paper into a single paragraph so you don’t have to, and fellow scientists can glance at this section to have a gist if this research is of interest to them. Next, I like to glance over the figures and figure captions to see a schematic representation of the authors’ work. Scientific figures can range from photos of their set-up, steps of their equipment or procedure, relevant imaging, and graphs for statistical analyses. Captions will explain each figure’s relevance to the study and state significant observations. Finally, I will read the actual paper. I like to start chronologically from the introduction, skipping the methods/results, glancing over the discussion for repeated or emphasized statements, and finishing with the conclusion. The conclusion is a helpful reiteration of any meaningful findings as well as some future directions for next steps.

On another note, scientists will often present their research as a visual poster at various conferences and presentations. The steps to reading a poster are similar to that of a paper, though much quicker because of the authors’ already summarized information and visual cues (e.g., larger text, bold/underline, different colors, more figures, etc.).